The Law Isn’t Fighting for Us – But Art Is.

In June, the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling affirming a constitutional right to abortion in the US. The decision was met with a global outpouring of anger, and helplessness, and fear, and my own body felt a kind of ineffable panic, a deep, visceral response to the knowledge that the law – those rules we made up and by which we live alongside one another – is broken, is breaking, is fallible.

Many people have written with greater knowledge and deeper insight than I possess about the repercussions of this event and its broader significance for both the US and the international sphere. What I want to consider here is perhaps best summed up by the artwork Barbara Kruger created in response to the ruling, a graphic work titled: If the end of Roe is a shock then you haven’t been paying attention. What Kruger puts forward, and what I discuss in this article within the context of my Irish upbringing, are two ideas. The first is a rallying cry against complacency, and the second an acknowledgment of the ways in which, when we believe the law to have failed us, art can take its place as an instrument of truth, freedom, and advocacy on the side of humanity.

Kruger’s response to the US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.

I grew up in Ireland, where the legacy and dominance of the Catholic Church is felt deeply in our social, educational and legal landscape to this day. In 2012, the tragic death of the young dentist Dr. Savita Halappanavar became a rallying cry for the “Repeal the Eighth” campaign in Ireland – “the eighth” being a long-standing constitutional amendment bestowing “the equal right to life” upon mother and “the unborn.” Under Irish law, Savita was denied an abortion even as she experienced a miscarriage, as a foetal heartbeat could still be heard. She was, chillingly, told: “this is a Catholic country.” After waiting a week for the heartbeat to stop, Savita died of septicaemia the following day.

A mural by the Irish street artist Aches depicting Savita’s face overlaid with the word “YES,” formed a visual focal point for the YES campaign in the lead-up to Ireland’s historic referendum on abortion in 2018. Through the medium of the mural, Savita’s death became a site of communal pain and resolve – a reminder of the essential humanity at risk behind the campaign slogans and academic jargon inherent to a divisive referendum. One message among hundreds written by the public around the image read, “for Savita, you made us fight. Never again.”

Mural by street artist Aches, surrounded by messages from the public.

Irish artist Jesse Jones has suggested that Ireland’s wider legacy of oppression against women amounts to a “dystopic social experiment.” The Irish mother and baby homes were most emblematic of this, run by Catholic orders across the country even until the 1990s to house women who had become pregnant outside of marriage (and who were accordingly ostracised by their families and communities). In 2017, the discovery of a mass grave of over 800 children at the site of the Bon Secours mother and baby home in Tuam, Co. Galway provided irrefutable, heartbreaking proof of the horrific conditions within which these women and their children lived, were forced to work, and in many cases died. Beyond this, until the 1980s it was illegal to buy contraceptives in Ireland, and as such women were unable to protect themselves from unwanted pregnancy or carry out any kind of family planning. And, until the 1970s, a marriage bar prevented women in Ireland from working in the civil service once they were married.

Jones’ body of work engages with the fight for women’s right to bodily autonomy in Ireland necessitated by this recent history. Jones has said that her initial desire to create Tremble Tremble, a vast cinematic installation, was as a means of grappling with what she saw as a “break in truth and language;” a break between the laws of a country and its people’s lived experience, particularly in the aftermath of Savita’s death. Thinking about the law “as something which could be estranged or made abstract,” Jones worked with lawyer Mairead Enright to construct a new, aspirational Eighth Amendment:

‘With regard to the moment when a human takes its place of dwelling in the maternal belly, it lives inside a giant. This giant is the only true origin of law. She possesses the double kindness: to create or destroy the life she carries. Her tenant is only temporary, its claim of occupancy finite. Its very existence not mere life, as we the living know, but the greater possibility of being or not being. It needs not the society of man to become manifest. It obeys the natural law of In Utera Gigantae – the world within the world made of flesh – not the state of land or sea or man or sky.’

Through this work, and the artist’s powerful command of language, Jones demonstrated how art might take on the responsibility of the law, embodying and emboldening truth and freedom when that very law is no longer in the best interest of those it is intended to protect. Tremble Tremble looks to the example of Italian scholar and activist Silvia Federici and the 1970s Italian Wages for Housework movement, in particular a chant which proclaimed “tremate, tremate, le streghe sono tornate!” (tremble, tremble, the witches have returned!).” The figure of the witch, performed by Irish actor Olwen Fouéré, suggests a matriarchal realm unfettered by Ireland’s centuries of oppression against women. In bringing together testimony, folk lyrics, and the artist’s own extensive research into Ireland’s history and laws, Tremble Tremble demonstrates how art can come to act as a site of active resistance.

Still from Tremble Tremble (2017)

Then, in 2018, I cast my first legal vote in the referendum which would successfully remove the Eighth Amendment, thereby legalising abortion in Ireland. A few years prior, Ireland had become the first country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage by popular vote. Given that in Ireland homosexuality was considered a criminal offence until 1993, and divorce illegal until 1996, my generation of young people in Ireland have grown up in a country undergoing rapid social and cultural change – and it seemed like a unidirectional trajectory.

The overturning of Roe v. Wade has exposed the hollowness of that assumption.

If the end of Roe is a shock then you haven’t been paying attention.

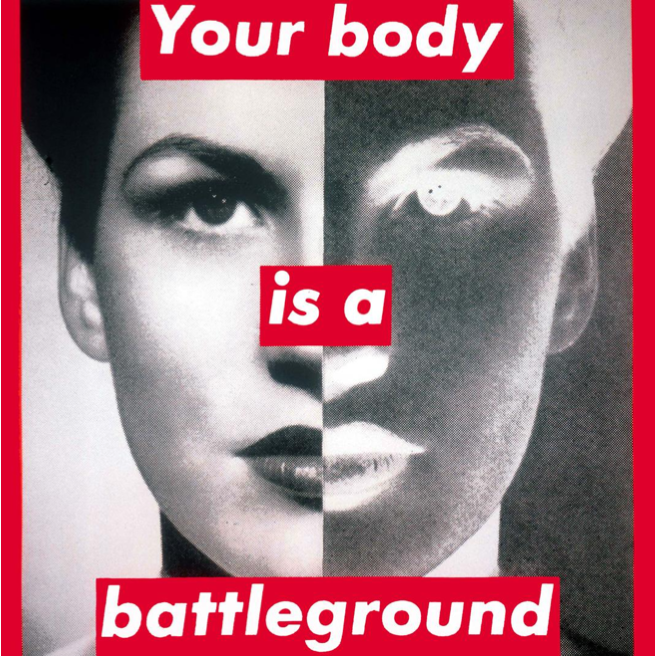

But Kruger has been; she first created her well-known artwork Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground) for the 1989 Women’s March in Washington, D.C., which opposed efforts (ongoing even at that time) to overturn Roe v. Wade. In 2020, Kruger revived the piece with a Polish-language version, working with feminist art collectives to plaster her poster across the country in response to new abortion legislation in Poland prohibiting abortion even in cases of “severe and irreversible foetal defect or incurable illness that threatens the foetus’ life” - this within a country already enforcing some of the most highly restrictive abortion legislation in Europe.

At the time, Kruger wrote of how “in the midst of a planetary pandemic, these events loom large and present possibilities for a dire and cruel future, but also might suggest something braver, more hopeful, and just.” The fear that “a dire and cruel future” might prevail was anticipated by the brilliant feminist artist Ghada Amer ahead of her London show My Body My Choice at the Goodman Gallery earlier this year. Speaking about the context of her exhibition, Amer suggested “in Western societies, there is an assumption, especially among the younger generations, that the battle of the sexes has been won, that women have been liberated, and that their rights are secure. And yet, we are witnessing today a sharp regression of women’s rights and a stark rise of violence against women.”

What the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade has made clear is the same thing Kruger has been telling us for decades: there is no winner in the fight for human rights; there is no finish line.

Kruger’s original 1989 piece Untitled (Your Body is a Battleground)

Kruger’s Polish-language version in the streets of Szczecin, 2020