Lifting Like a Girl: An Art-Historical Perspective

We’ve all heard it (some might have even said it)—the oft-pronounced verdict of ‘this is not feminine’. As a committed gym-goer, I am most of all concerned with the idea that strong women are just not ‘feminine’.

Women with muscles? Not feminine. Abs on women? Not feminine. The list goes on. It is saddening that even in our modern day and age of fourth-wave feminism women who do not follow an ideal of slenderness are often subject to advice such as ‘do not do A to your body because men don’t like that’. I find this particularly disturbing when it comes to athletic women and the phrase ‘you don’t want to intimidate men’. I mean, don’t I? And what is the saddest bit is that more often than not such judgments are pronounced by other women. What is lost is an obvious, yet always overlooked fact—a woman’s body’s relationship to muscularity has rarely if at all been informed by a wish to appeal to male standards of beauty. Hence, in what follows, I’d like to submit this kind of discourse to a long-overdue revision. Art history will lead the way.

Fortunately, the question of women and muscularity has been discussed before, a most useful example being David L. Chapman and Patricia Vertinsky’s book Venus with Biceps. This is a visual survey of strong women spanning the period 1800-1980. What is omitted, however, is the fact that representations of muscular women are not a modern phenomenon—they go back to the times of Antiquity. My favorite example is the Roman mosaics at the Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily, known as the ‘Bikini Girls’. Dating from 310 CE, the scene of the ‘Bikini Girls’ depicts ten scarcely clad female athletes. One of them is holding dumbbells, while another is preparing to throw a discus. Since this clearly depicts a sports competition, there is also a scene of the crowning of the winner. Now, when this prime example of female athleticism was excavated in the 1960s, archeologists thought it was a beauty competition. Lo and behold, a woman training with weights! See, they could not even imagine a scenario where women could use dumbbells. Funny how history has a way of quoting itself—I’m reminded of contemporary competitions such as the World Beauty Fitness and Fashion (WBFF), which features a bikini sub-section. The Romans, then, valued a defined female physique no less than they did a male one. Let us see how this reappears during the Renaissance.

The ‘Bikini Girls’, 310 CE, Villa Romana del Casale

Michelangelo, Lybian Sybil, 1508-12

Michelangelo, Studies for Lybian Sybil, 1508-12

The most cited example of female muscularity during the Renaissance is the majority of Michelangelo’s women who are undeniably ‘masculine’ in their appearance. I have even seen them referred to as ‘men with tits’. The women depicted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel are a prime example. There are several theories that have been proposed as potential resolutions to this drama of ‘androgyny’. One suggestion is that female models were simply not available at the time, so artists resorted to the male physique with which they were more familiar. I consider this naive—artists during the Renaissance were not celibates. Another possibility is the fact that Michelangelo was gay so perhaps he was projecting his own desires onto both his male and female subjects. This is possible albeit not very plausible since we know for a fact that he was perfectly capable of sculpting ‘feminine’-looking women such as his famous Pieta. Instead, I suggest another answer. The Renaissance was a period when the male nude was considered the ideal type of human physique, so the muscularity normally associated with men was not necessarily a male thing in itself. Rather, it was a telltale sign of a superior human body. This included the female body. Furthermore, it is indicative that depictions of muscular women during the Renaissance were mostly centered either on women who were engaged in some kind of action or represented an allegorical/biblical figure.

A beautiful example is Michelangelo’s Lybian Sybil on the Sistine Chapel ceiling—she was an important prophetess and priestess overseeing the Oracle of Zeuz-Amon in the Lybian desert. Meaning, she was a woman who pushed forward the course of history. When we look at the study of her figure, we see how much attention was given to the definition of her every muscle. Another example is Giorgio Vasari’s rendition of Judith slaying Holofernes—she is absolutely ripped. Our eyes are immediately drawn to her well-defined back and arms. Her figure exhibits sheer strength. Renaissance thinking also tended to equate bodily characteristics to intellectual and temperamental virtues. As a woman on a mission to save her people, Judith needed to exhibit both kinds of virtue. I personally believe that this kind of representation was probably not far-fetched in the early modern period. After all, most women had to do a lot of physical labor in the form of household chores. Moreover, it is interesting to note that later on, in Rococo, Impressionist, and Symbolist paintings, the ideal of female beauty shifted towards a more slender, passive type. Interestingly, most of the women depicted in such images are idle women. Note for example Raimundo de Madrazo’s Reclining Lady.

Giorgio Vasari, Judith and Holofernes, 1554

Raimundo de Madrazo, Reclining Lady, date unknown

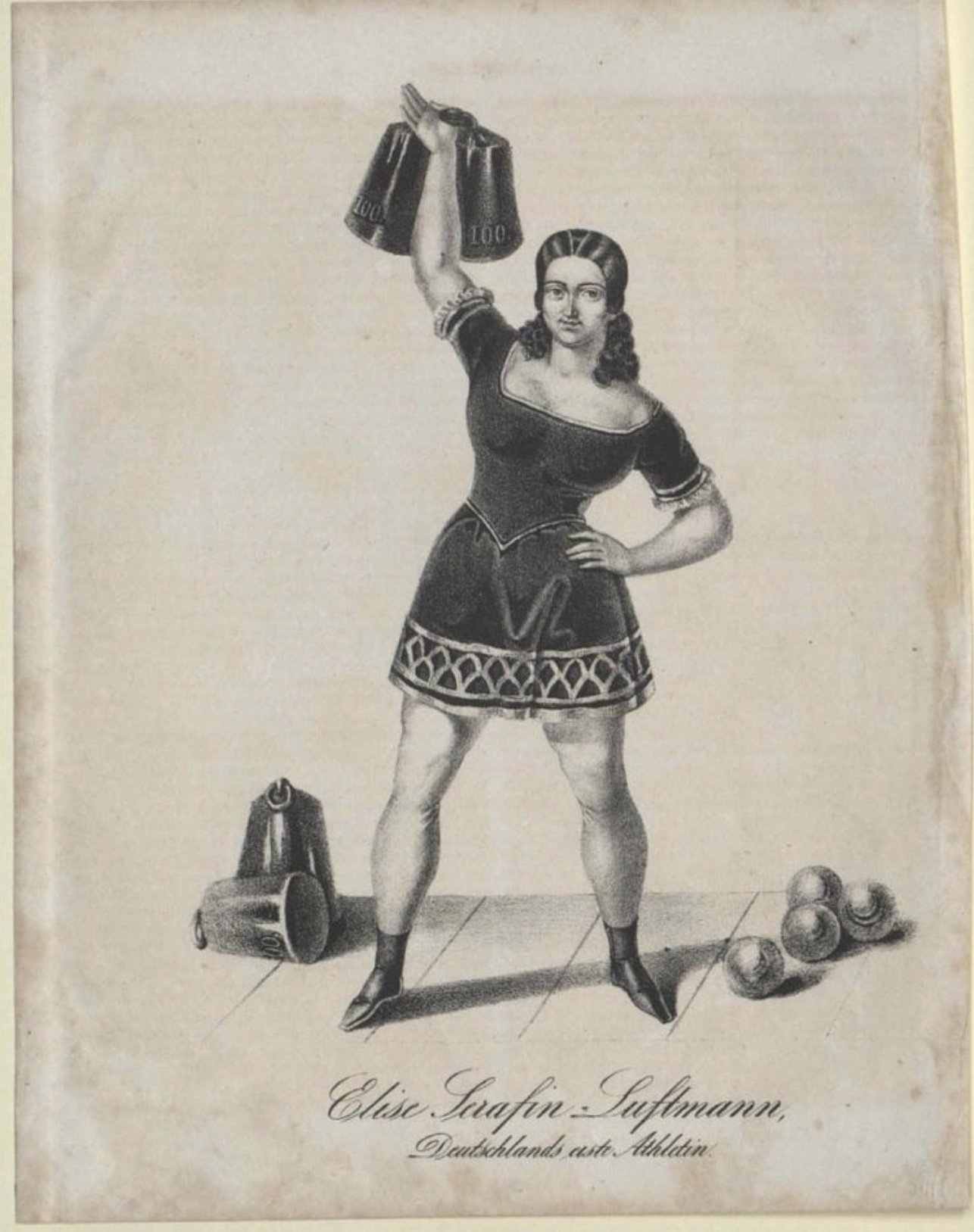

Therefore, by the 1800s, when the survey of Venus with Biceps begins, female beauty standards in relationship to muscularity and sports had obviously changed. Muscle building as a specific type of sport was born during the Industrial Age when health and one’s physical condition became a subject of attention. Female athleticism in particular was seen as conducive to moral degradation and potential ‘unsexing’ and ‘undesirability’ of a woman’s body. This is strikingly similar to contemporary criticism of female bodybuilding. Ultimately, this stems from gendered anxieties about female weakness and passivity and male activity and strength. An example of how this thinking manifested during the late nineteenth-early twentieth century is the category of the ‘strongwoman’. These women were exceptionally strong and competed in strength athletics. They were basically the trendsetters of contemporary bodybuilding culture.

Elise Serafin Luftmann, Strongwoman, c. 1835

Naturally, such women were upsetting to the status quo as they emphasised women’s biological possibilities as equal to those of men. Where might such dangerous, abnormal women find the space to be themselves? You guessed it—at the circus. After all, this was at a time when women were advised to stick to graceful and feminine sports such as rhythmic gymnastics. I am not joking when I say (having briefly experienced the pain and joy of rhythmic gymnastics at the tender age of 5) that this is still the standard in many European countries. Ultimately, the fact that strongwomen existed despite societal marginalisation is the biggest proof, still relevant today, that women’s bodies are spaces on which we all perform deeply intimate and personal choices. We do not work on them to please others or because we have something to prove. It is true however, that body discourse is a very contemporary thing indeed. As Vertinsky puts it, ‘in terms of how we feel about ourselves physically we may be worse off than our unliberated grandmothers’. And this is precisely because of such outdated, rigid, and frankly ridiculous conceptions of femininity that allow people to continue assuming that something is or is not ‘feminine’. As some historical examples show, divorcing women and physical strength is an entirely modern fabrication.