Entertainment for a Lost Milieu: Alaska Lynch’s Vaudevillian Universe of Obscurity

I first met Alaska Lynch at a hill-top party in Laurel Canyon that asked guests to come dressed as either a black cat or a red elephant. Neither of us were in costume. My friend and I walked up to him at the end of the night—sometime around 4 a.m.—as he was donning a triple-breasted suit jacket and a black briefcase. “Do you enjoy formal dinner parties?” he asked. We looked at each other amusedly before answering that we did. This all took place before names were exchanged.

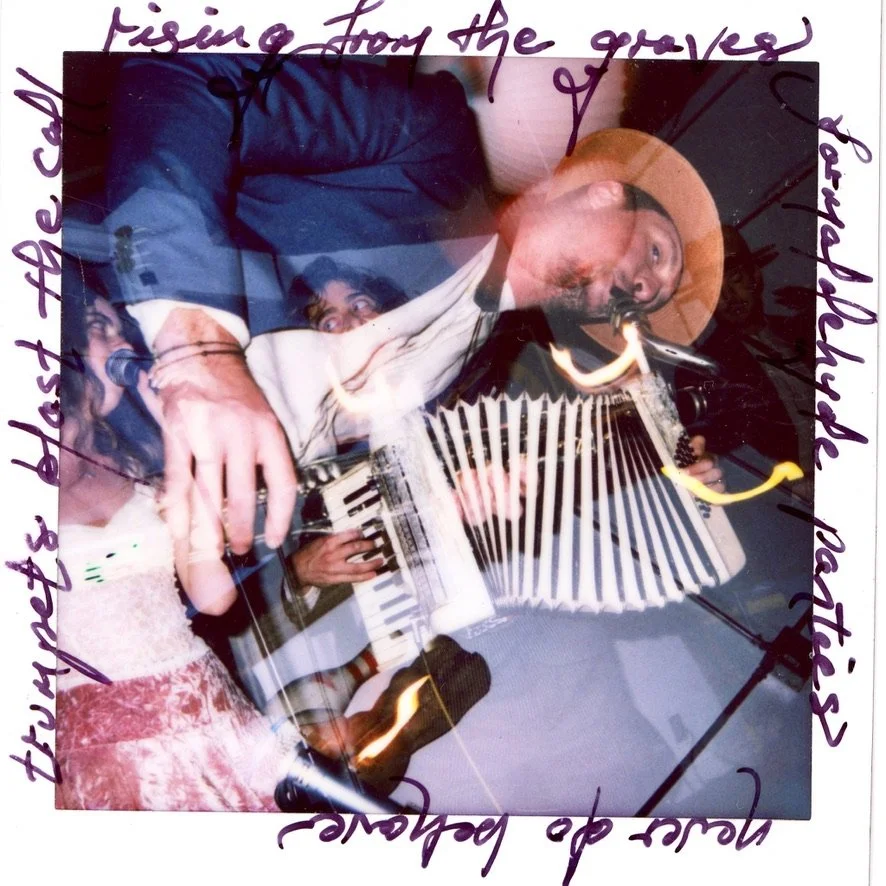

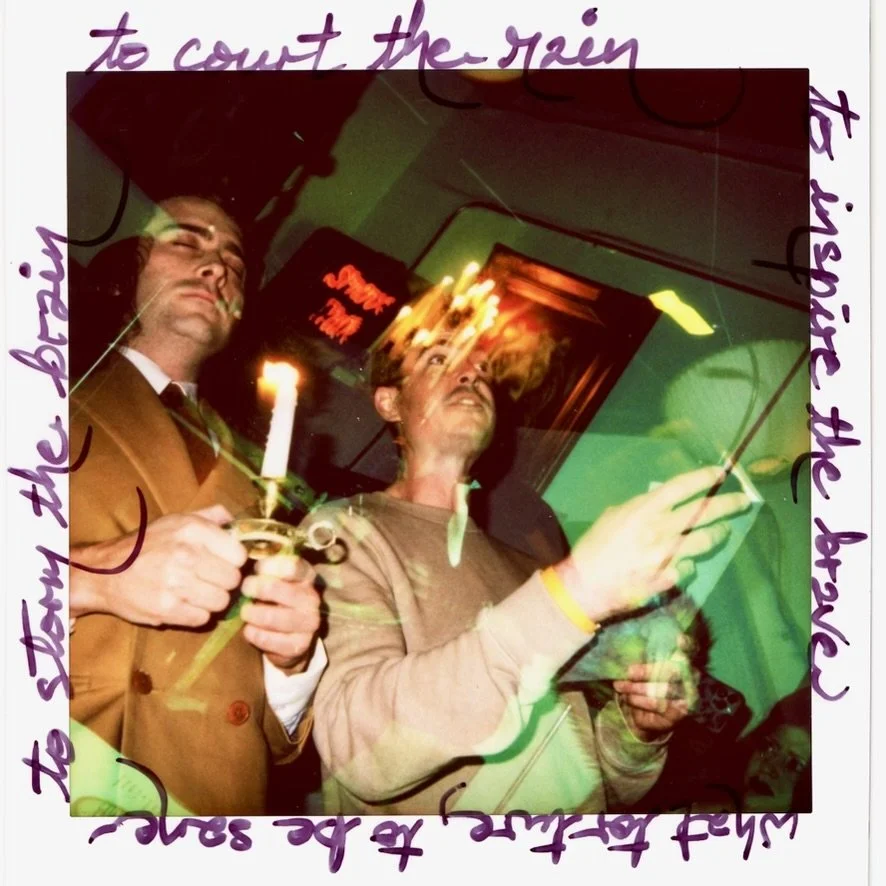

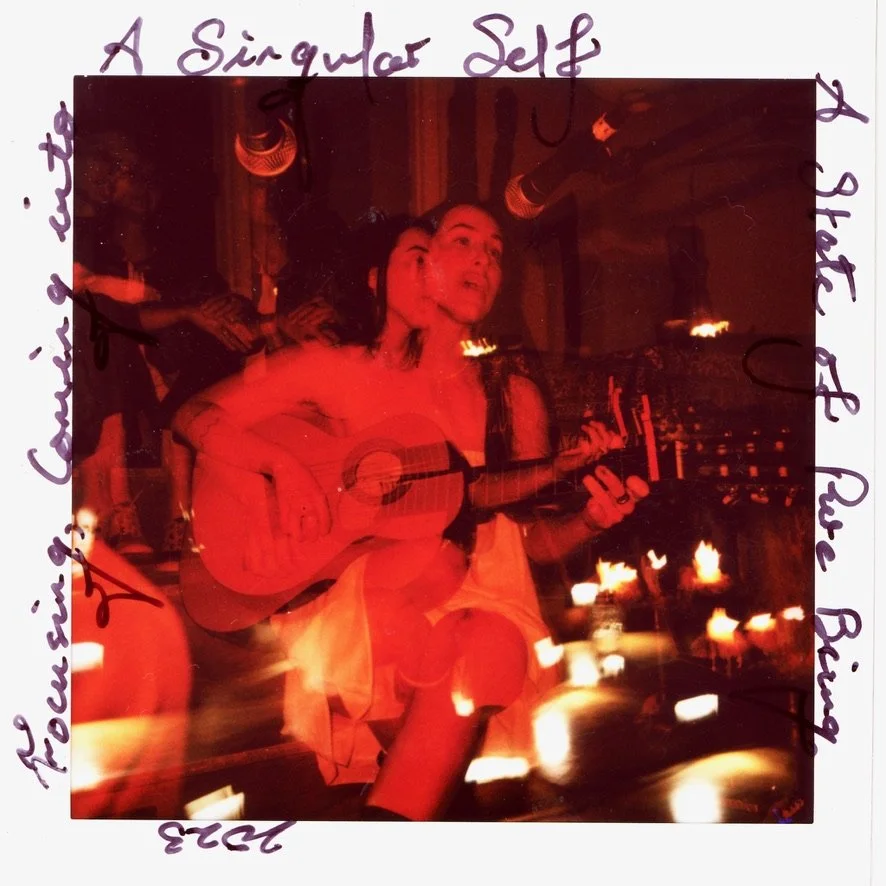

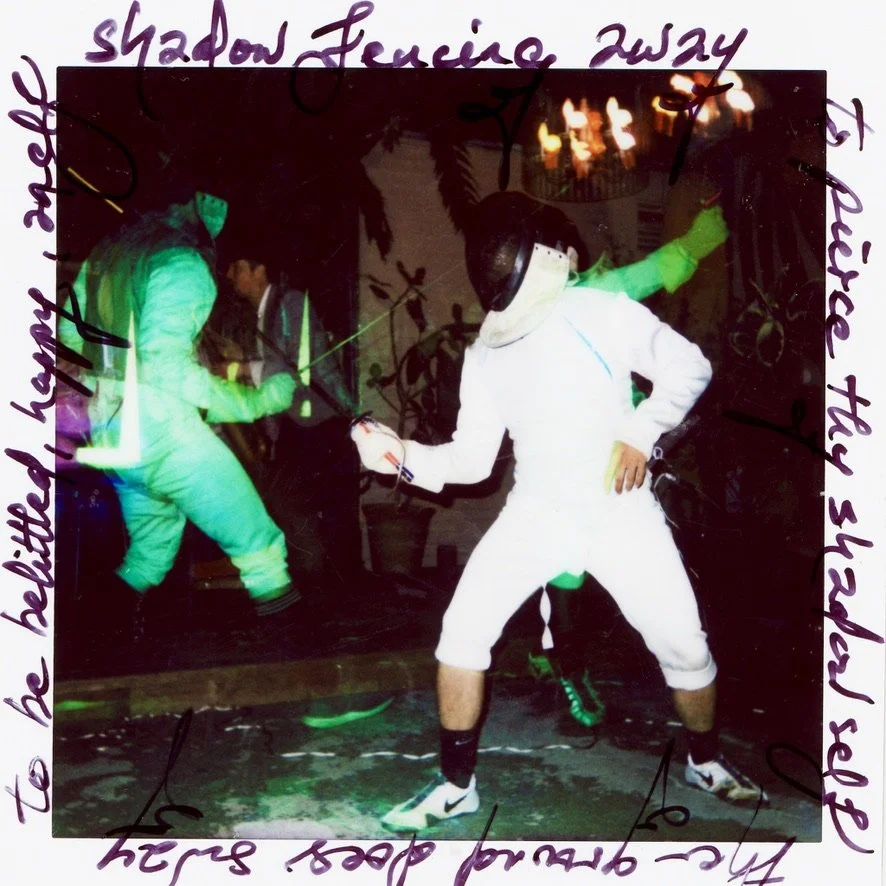

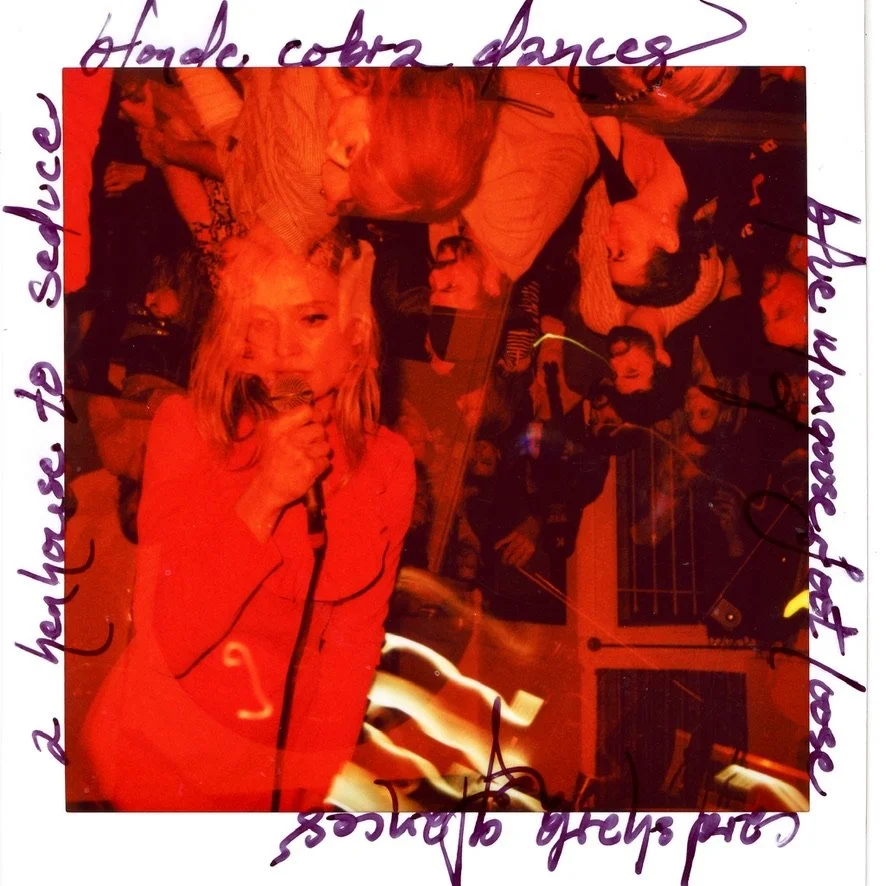

Historically, Los Angeles has been home to quite a few eccentrics. Alaska is no exception. A writer, accordionist, theatrical host, and the 2019 Poet Laureate of GUCCI, he holds no shortage of talents to regale the public with. In 2023, he started hosting a monthly variety show dubbed “Baiting the Gods,” an eclectic showcase of live music, poetry, and avant-garde performance (the one I attended had two fencers duke it out while orchestral music swelled in the background). He also co-founded a theater non-profit “Temporal Refugee Foundation” (TRF) with his cousin, Joan Lynch. Before their last show, Alaska came on stage with a wax candle on his head and, speaking in a Shakespearean lilt, said,

“In my youth, I consumed way too much media, and as a result I feel displaced from the present. I am a temporal refugee, and maybe… you are too!”Alaska’s theatrical universe is completed by his supperclub “Pink Serpent Supperclub,” a 20-person, 4-course dinner, accompanied by short plays and dinner games in which guests design the rules for a post-apocalyptic religion. At its last iteration, Alaska had a demure woman in black lace read from Anaïs Nin’s Incest as a part of this world building.

These events, rooted in the present but also pointedly anachronistic, come to us at a peculiar time. We’re living in an era fettered by technological solipsism and a waning effort to socialize. The ubiquity of digital technologies, social media, and odiously scripted television is numbing our brains towards oblivion. Binge-watching shows like Emily in Paris is the laudanum of the modern age, blanketing our anxieties to the point of drunken sedation.

According to a study in the Journal of the American Planning Association, our inward retreat, measured by “a pronounced shift of activities into the home and a concomitant reduction in time spent traveling,” has been going on since 2003 and was acutely amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic. Academic psychiatrist Dr. Stephen Rush claimed that during the collective trauma of the pandemic, “keeping yourself isolated was actually a way of protecting yourself that, now, has been integrated into people's defense mechanisms.”

Our post-pandemic world, coupled with the onslaught of new technology, has gotten us into a bit of a fix. We are all in a polyamorous, codependent relationship with our screens. The despotic rule of the algorithm is unfortunately triumphing over our better judgement.

However, there is an emerging trend of events and spaces curated towards community building in the face of digital isolation. No-phone events have become increasingly popular, with festivals, concerts, and restaurants adopting the approach. “More of us,” writes Joelle Renstrom for Psyche, “seem poised to push back against the ubiquity of phones in favour of prioritising firsthand experience.” A slew of digital detox events have also cropped up, including off-the-grid retreats where, as Shannon Sims reports for The New York Times, “travelers opt into an internet-free environment.” These efforts reveal a collective hunger for something that has been significantly diminished over the past few decades: connection.

Alaska’s universe, while tangential to this trend, is by no means defined by it. His events don’t just create connection, they revolutionize it. They are cemented in a deep solicitude for novel, and often radical, efforts to cultivate community.

“We’re saturated with music and experiences, but there’s a lack of connection and narrative,” says Evan Volk, co-founder of the venue In The Meantime, where “Baiting the Gods,” “Temporal Refugee Foundation,” and “Pink Serpent Supperclub” take place. “Alaska curates a show that feels like you’re back in a salon before media was invented; it’s communal, electrifying, and never typical. There’s a high to it that we’ve been subconsciously searching for.”

Viewers are challenged, Alaska says, “not to be in a state of pure voyeurism.” There’s always a level of crowd involvement and movement. Even during their theater programs, Joan and Alaska invite audience participation through a giant wheel segmented into Jungian archetypes that gets spun at the end, which decides the theme for the next showcase. “When we spin the wheel,” Joan explains, “we often have the audience chant things… it’s a way for everybody to come together at the end and feel like they were a part of something.”

Rather than inundate us with hackneyed mantras about how important it is to breathe, as so many wellness and digital detox platforms tend to do these days, Alaska’s events cultivate presence via a more circuitous and unsuspecting route: by returning to the past. In our day and age, and arguably for the past couple of decades, too, entertainment has fallen under the dominion of mass production. I live in Hollywood and every week I see a new poster or billboard brandishing the name of some horrible-looking film or TV show. Much of what’s produced has lost what Walter Benjamin calls the “aura”—something’s unique existence in time and space—and no longer serves to help us experience and navigate the present. As a remedy, Alaska fosters environments that allow us to return to those times when quality was paramount and the “aura” of things was still intact; wherein we may witness something not as a bemused spectator, but as a quasi-thespian, immersed in the drama of it all.

Far from adopting the jingoistic reverence for the “good old days” that have corroded the American government (“Make America Great Again”), Alaska is much more nuanced when looking to the past for inspiration. He’s not a full-blown luddite hell-bent on giving up the digital age completely, nor does he eschew the progressive benefits that have arisen in the last century. He acknowledges the importance of synthesizing different paradigms of existence to make room for an accommodating present.

Alaska said that “Baiting the Gods” had initially been a no-phone event, but that the policy was too difficult to enforce. It was better to let the intermittent screen rise above the crowd rather than to admonish people constantly. At the last TRF, he told everyone to put away their cellphones, and then added, “But not just yet, because you’re going to want to record what’s about to happen.” We’re creatures of habit. A total renunciation of technology’s omnipresent role in our lives isn’t going to happen overnight. Alaska knows this, and is willing to make a joke about it.

Phone out or not, these events are sure to captivate even the shortest attention span and rescue us from our existential emaciation. I, for one, am thankful that “Pink Serpent Supperclub” was there to save me from another night of eating Trader Joe’s vegetable gyoza and streaming Succession on my laptop. Sitting around the oblong, wooden table while piano maestro Pàppa D (otherwise known as “The Greek Spider of the Keys”) soundtracked us into an ethereal jouissance felt as if I was caught in a lucid dream, where neither reality nor fiction took precedence, and everything was melded together in timeless revelry. It was like an episode from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, where the characters, guzzling down champagne and crudités, erratically launched into monologues about existentialism and romance. The food, while good, was auxiliary. There was a more important appetite being sated: that of our souls.

Alaska’s universe belongs to a lineage of performers, artists, and partygoers who sought communion during periods of isolation. Lois Long, who anonymously penned the nightlife column “When Nights Are Bold” for The New Yorker during the Prohibition, wrote under circumstances, which, a century later, are much like our own: surveillance, seclusion, and dogmatic politics. Nonetheless, Long’s tone was extravagant and acerbic, describing her surreptitious rendezvous with pomp and even a bit of backlash against the strictures of the time. Her writing stands as a testament to the power of connection and celebration in the face of a disassociated, sociopolitically oppressed present.

Like Long, Alaska is carving out experiences for a lost milieu—a generation hungry for something real in an age that refuses to dole out anything but breadcrumbs. At the center of which is a rhetoric that challenges the complacency of the status quo and charts a philosophy geared not only towards community, but an entirely new reality, too.

A reality that decries banality, mediocrity, and mass production, and revels in disruption, chance, and idiosyncrasy. In a world that seems intent on its own destruction, perhaps the post-apocalyptic religion Alaska had us devise at his supperclub wasn’t just for fun. Perhaps his Vaudevillian whirl of madness, humor, and eccentricity is prepping us for something bigger. Something real. A poetic afterlife in which community is no longer a privilege but a guarantee.

For more information about “Baiting the Gods,” “Temporal Refugee Foundation,” and “Pink Serpent Supperclub,” please visit the following Instagram pages: @baitingthegods, @temporalrefugeefoundation, and @pinkserpentsupperclub.

Cascades of thanks to the numerous photographers: Noa-Marie Ribot, Deva Holliday, Emma Volodchinskaia, Shaina Rose, Chelsea Alexander, Joan Lynch, Alaska Lynch.